Jasmine Wali

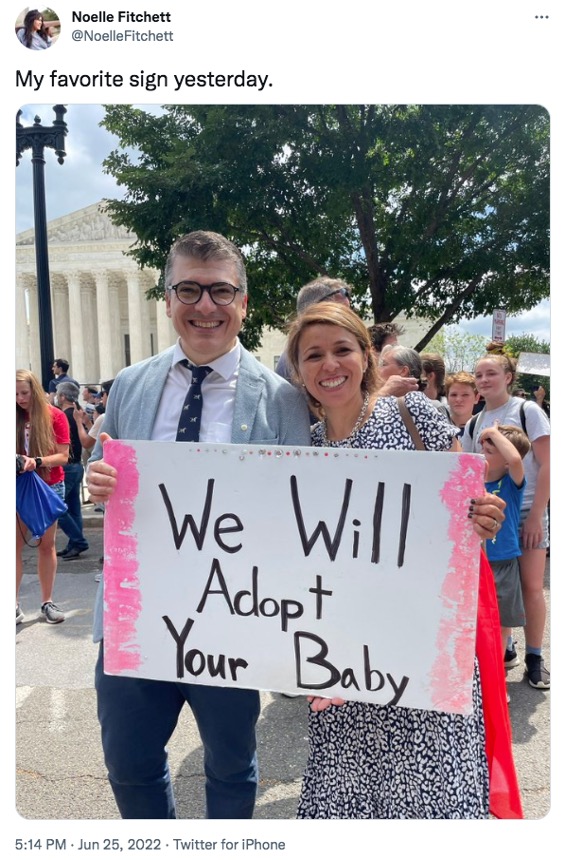

When Roe v. Wade was overturned, advocates across the political spectrum declared that the foster care system would be overwhelmed by an influx of “unwanted” children. Adoption became a central talking point. Anti-abortion proponents stated that adoption was a solution for these families, and that foster and adoption systems needed to be strengthened. Supporters of reproductive choice pointed out the seeming hypocrisy of the “pro-life” movement by highlighting all the children awaiting adoption in foster care.

Using foster and adoptive systems as either an alternative to abortion or as a talking point around the topic of abortion demonstrates a fundamental belief about children in these systems: that they are unwanted. The swift connection the public made between banning abortion, more “unwanted” children, and an overwhelmed child welfare system is steeped in history.

In 1975, famed columnist and psychologist Joyce Brothers wrote in the Chicago Tribune: “For many parents, child abuse amounts to retroactive abortion,” opining that parents subconsciously attempt to get rid of their children through perpetual abuse when they realize they do not want their child. A 2002 study found that limiting abortion availability increased reports of child maltreatment (which includes reports of neglect), and concluded that parents with unwanted pregnancies are therefore more likely to abuse or neglect their children.

Foster care fact sheets conflate abuse with neglect, perpetuating the narrative that parents whose children are in foster care are “unfit,” and children are rightfully saved from these abusive homes by Child Protective Services (CPS), foster caretakers, and adoptive parents. However, the majority of children in foster care are removed for neglect, which is better understood as a symptom of poverty.

The abortion debate has long been guided by conservatives’ perception of immorality. The modern-day child welfare or family policing system is also guided by a racialized and gendered understanding of immorality. When an act or a person can be deemed immoral, they can be criminalized. Abortions can be outlawed and “immoral” parents can be punished with family separation. Understanding these links as opposed to perpetuating notions about families ensnared in the family policing system can deepen our understanding of reproductive justice, which entails not only the right to maintain bodily autonomy but also the right to parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.

“Illegitimate” and “Unwanted” Children

In 1962, pediatrician C. Henry Kempe and several colleagues published the article The Battered Child Syndrome about child abuse. The report described a child being “unwanted” as a considerable risk factor for parental violence against the child. It also introduced the empirically unsupported idea of parental violence against children as a diagnosable and treatable medical condition or mental illness, and allowed for physicians to maintain ownership over this complex social problem and guide its interventions.

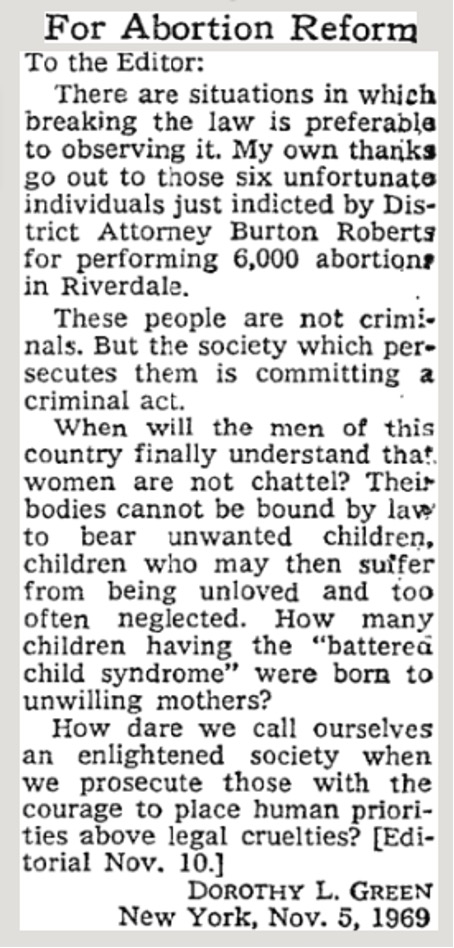

The Battered Child Syndrome (BCS) was extensively reported on over the next decade by popular media, fueling public concerns over the supposed epidemic of child abuse plaguing “unwanted” children. The public was quick to link this phenomenon to abortion rights. In 1969, The New York Times published a letter to the editor that directly tied the theme of abortion access to the “Battered Child Syndrome.”

Following the publication of BCS, researchers across the country mobilized to conduct their own studies of child abuse. Data points gathered went beyond typical categories such as age, sex, and ethnic background to include the categories of “legal status of victim” (i.e., “legitimate” or “illegitimate”), “whereabouts of victim’s biological father/mother,” and how much public assistance parents received. Collection of these data points were used to form a narrative about families reported for suspected child abuse, and mirrored terms and themes salient in other public debates around Black families and welfare.

The Battered Child Syndrome led to the Social Security Act being amended in 1962 with a new emphasis on Child Protective Services and identifying risk factors and reporting, leading states to develop their own systems for mandatory reporting.

Discourse About Black Families

In 1965, amid the Civil Rights Movement, Lyndon B. Johnson’s Assistant Secretary of Labor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, wrote the Moynihan Report with the goal of persuading the Johnson Administration to move swiftly to improve the plight of poor Black families through federally financed anti-poverty programs. However, the report’s focus on the Black family structure provided a convenient rationalization for inequality.

In the report, Moynihan writes about Black families:

“Nearly One-Quarter of Negro Births are now illegitimate.”

“Most Negro youth are in danger of being caught up in the tangle of pathology that affects their world … At the center of the tangle of pathology is the weakness of the family structure … In every index of family pathology – divorce, separation, and desertion, female family head, children in broken homes, and illegitimacy.”

“Drunkenness, crime, corruption, discrimination, family disorganization, juvenile delinquency were routine of [Irish slums of the 19th Century]… [and] has produced the Negro slum… fundamentally the result of the same process.”

The Moynihan Report is understood to be a foundational text in the development of War on Poverty policies. While Moynihan discusses the role of systemic racism in perpetuating wealth disparities, he also argues that the increase in welfare dependency can be “taken as a measure of the steady disintegration of the Negro family structure,” aligning with conservative politics of personal responsibility and associating blame for poverty and racism to individual Black families. Conservatives used the report to reinforce racist stereotypes about loose morality among Black families.

The controversial report has been criticized for stigmatizing Black men and marginalizing Black women, the timing of its release (coinciding with Civil Rights protests while reinforcing violent stereotypes about Black communities), and its failure to address the impacts of job discrimination and racism on unemployment rates.

The Battered Child Syndrome and the Moynihan Report used similar terms to describe parents who physically abused their children and Black parents. Children were characterized as “unwanted” or “illegitimate.” Substance abuse was described as “alcoholism” or “drunkenness.” Parents were diagnosed as “psychopathic and sociopathic” or “pathologic.” Families were defined by “sexual promiscuity, unstable marriages, and juvenile delinquency” or “divorce, separation, and desertion, female family head, children in broken homes … family disorganization, juvenile delinquency.”

The confluence of the BCS and the Moynihan Report, published only three years apart, conflated parents who abuse their children with Black parents. Both reports criminalized parents, questioned supposed sexual morality, and ascribed a set of treatments to address presumed personality traits and family structure.

Perceptions of Welfare

Welfare discourse was shifting in the 1960s, too. Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was one of a number of social safety programs created with the Social Security Act of 1935, but had largely excluded Black parents. As a result of the Civil Rights Movement, single Black women began gaining access to these AFDC welfare benefits. “Welfare” began to conjure a racialized and sexualized image as more Black women joined the welfare rolls and concepts of morality and worthiness for government help became defined by a woman’s marital status when she had children. Historian Premella Nadasen notes that “promiscuity and laziness became synonymous with Black women on welfare,” and that “‘illegitimacy’ became a catchword for evidence of the degeneracy of the Black population.”

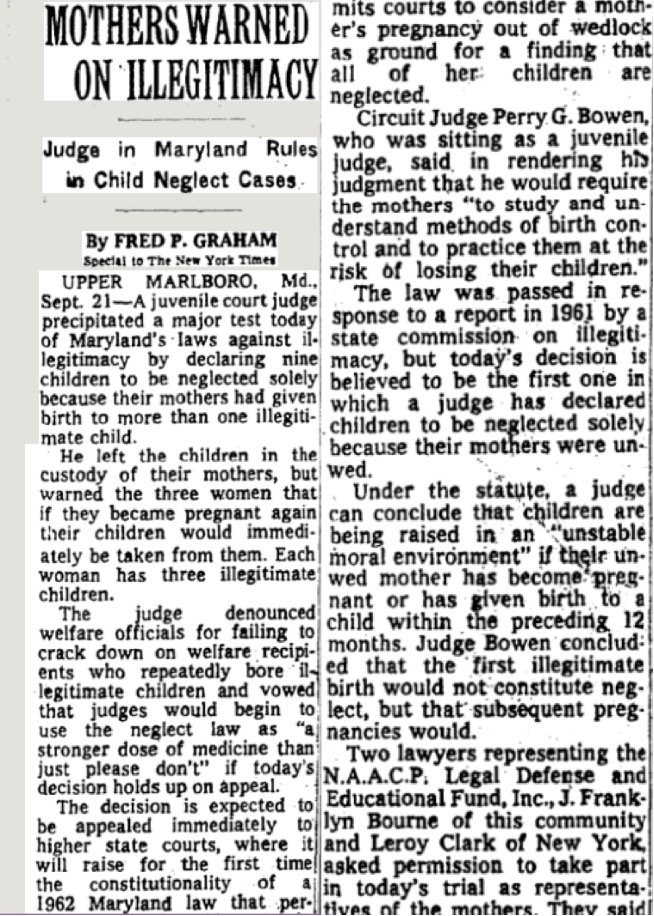

This public shift on welfare was immediately tied to reproductive justice issues. Numerous legislative proposals included punitive actions for parents of “illegitimate” children, including the loss of welfare benefits, sterilization, the imprisonment and/or fining of the parents, the loss of custody of the children, and various combinations of the above.

Vague definitions of neglect could be legally interpreted to criminalize poor Black women and deem them “immoral.” A 1967 ruling in Maryland courts left a mother at risk of losing custody of her children based on a state law that permitted courts to consider pregnancies out of wedlock as grounds for a neglect finding for failing to provide a “stable moral environment.”

These three focal points of the 1960s–child abuse, the Black family structure, and welfare–coalesced around attitudes on immorality. Media reports heightened the public’s sense of urgency for policies to address children, or “immoral” parents would go on to abuse their children, generationally drain government resources through welfare, and commit crimes.

Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act

To promote child well-being, Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale championed the Comprehensive Child Development Act, which would have created a universal network of federally subsidized child care centers. This multi-billion dollar investment was passed by the House and Senate with bipartisan support, but President Nixon vetoed the bill in 1971. In his veto speech, Nixon claimed that the bill represented a “communal approach to child-rearing” and had “family-weakening implications,” echoing concerns over family morality, and purposefully disparaging the importance of community and governmental support.

In response to the veto, Mondale, who still saw a need for a federal program to address child well-being, pursued the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA). CAPTA authorized funding for the identification and supposed prevention and treatment of reported child maltreatment, reinforcing a medical model in which child abuse was a psychological failing of parents and could be prevented through behavioral change and personal responsibility.

Many scholars have argued that CAPTA created a false equivalence between intentional physical harm to children by their parents and conditions of poverty. By codifying poverty as parental neglect, CAPTA circumvented discussions about race and class, absolving the government’s responsibility from addressing structural, economic, and racial inequities shaping children’s well-being, and placing the onus of child wellbeing on individual parents.

Today’s welfare programs continue to uphold the values set by CAPTA and anti-welfare rhetoric of the ‘60s and ‘70s. AFDC became the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program in 1997. According to 2019 federal records, Mississippi–the state behind Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health and home to the highest welfare rejection rate–spent only 5% of its TANF block grant on cash assistance (providing just $260 per month for a family of three in 2022). Meanwhile, it spent $27 million, over five times the amount of cash assistance, on the state’s Child Protective Services and foster system. Twenty-six million dollars of Mississippi’s federal TANF dollars were spent on the state’s “Fatherhood & Two-Parent Family Programs,” echoing the Moynihan Report’s statements about the absence of fathers and the need to rectify the moral structure of the Black family.

Abortion Seekers and the Foster System

According to the Guttmacher Institute, the majority of people seeking abortions are already parents. Seventy-five percent of people seeking abortions are low-income and nearly half live below the poverty line. More than half have just experienced a disruptive life event, such as losing a job, breaking up with a partner, or falling behind on rent. One study found that the population of abortion seekers who are unable to access a provider in a post-Roe world is likely uninsured, working in shift/low-wage jobs with unaccommodating schedules, and unable to go out of state due to travel, childcare costs, and/or disability. Reduced abortion access disproportionately affects Black women and birthing people.

An amicus brief from 154 economists filed against Dobbs regarding the potential economic impact of Dobbs cited the causal relationship between lack of abortion access and increased poverty. People who are denied an abortion experience a large increase in sustained financial distress and reduced credit access. Studies show that birthing people experience an immediate and persistent one-third drop in expected lifetime earnings once they give birth, and are more likely to stay in abusive relationships.

Poverty is the leading reason families get reported, investigated, and separated by the family policing system. Hardships that inevitably accompany poverty–such as food insecurity, lack of childcare, utility shut-offs, health care costs, and homelessness–all increase the risk of involvement in this system.

Racial disparities exist at every stage of the family policing system. Implicit racial biases held by mandated reporters (i.e., teachers, counselors, and healthcare providers), CPS investigators, foster agency staff, and family court judges accompany assumptions regarding socioeconomic status, and contribute to these disparities.

Over half of all Black children will experience a CPS investigation. Despite similar rates of substance use between Black and white pregnant people, Black people were 10 times more likely to be reported for substance use during pregnancy, often leading to newborns being ripped from their parents at the hospital. Once in the foster system, Black children are kept out of their homes for longer periods of time than their white counterparts. Black parents also experience Termination of Parental Rights (TPR) at higher rates than white parents; disabilities add to disproportionate separations and termination of parental rights. Once a parent’s rights are terminated, the child is put up for adoption.

Maintaining employment, especially shift/low-wage work, is often in direct conflict with successful reunification. Parents must attend parenting classes, supervised visits, court proceedings, and other “preventive” services to stay on track for reunification. Shift work can necessitate a reliance on informal childcare arrangements, which can be deemed inadequate by the family policing system. Many parents must quit their jobs to have a chance at meeting complex reunification requirements, plunging them further into poverty.

Strengthen the Social Safety Net

An influx of children into the foster system resulting from Dobbs will more likely be due to forced birth causing poverty and the criminalization of poverty by the family policing system. Assumptions that banning abortions will lead to increased child abuse repeats 1970s-era rhetoric that there is an inherent pathology and criminality among Black parents who are too poor to access reproductive healthcare, and strengthens the arguments for unconstitutional state investigations and intervention.

Parents impacted by family policing and family defense advocates have long called for investments in the social safety nets that support and strengthen families. Instead, welfare programs such as AFDC and childcare were defunded or vetoed as the modern family policing system took shape in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Up to 30% of foster children could be home right now if their parents had adequate housing. Anti-poverty programs today, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit, childcare subsidies, medicaid expansion all reduce reports of child maltreatment. A recent study found that increasing the minimum wage by $1 reduced reports of child neglect by nearly 10%. Increased provision of material services–food, clothing, utilities, housing, transportation, and other concrete supports–led to reduced reports of child maltreatment over a longitudinal period. Understanding that symptoms of poverty are reported as maltreatment and neglect makes the solution for the foster system crisis apparent.

The third of abortion seekers who do not have the means to access an abortion will be further pushed into poverty. The same intersections of race, class, gender, and disability that inform access to abortion are also surveilled and criminalized by the family policing system. Advocates for reproductive justice must understand that the same concepts of immorality that have shaped the Dobbs decision also shape the family separation crisis.

Jasmine Wali, MSW, is the Director of Policy & Advocacy at JMACforFamilies and a practicum instructor at Columbia School of Social Work.